Urvashi Vaid’s vision of the ongoingness of politics

“I believe social change happens both incrementally and in flashes of illumination.”—Urvashi Vaid

In this moment of rising authoritarianism and the Trump administration’s aggressively regressive politics of cruelty, it can be helpful to return to an earlier moment to understand both the right-wing’s sadistic and dehumanizing rhetoric and policies and the creative response by people in the face of such dehumanization. All my work explores the multiple spaces and temporalities of illness and illness politics, and HIV/AIDS was the illness that first made me pause to consider how illness transforms everyday experiences of time and space. In the year since Trump’s second inauguration, I have found myself returning to writers, artists, and activists who responded to the AIDS crisis in the period between when it was first identified in the early 1980s and when treatments became available in the mid-1990s, transforming AIDS from an almost-universally deadly condition to a treatable chronic condition, at least for people who had access to the treatments. For me, Duke University Press’s publication of the selected writings of Urvashi Vaid in a volume titled The Dream of a Common Movement has come at just the right time. I suspect there are many of us who need this book, and Vaid’s vision, now and for other possible futures beyond authoritarianism.

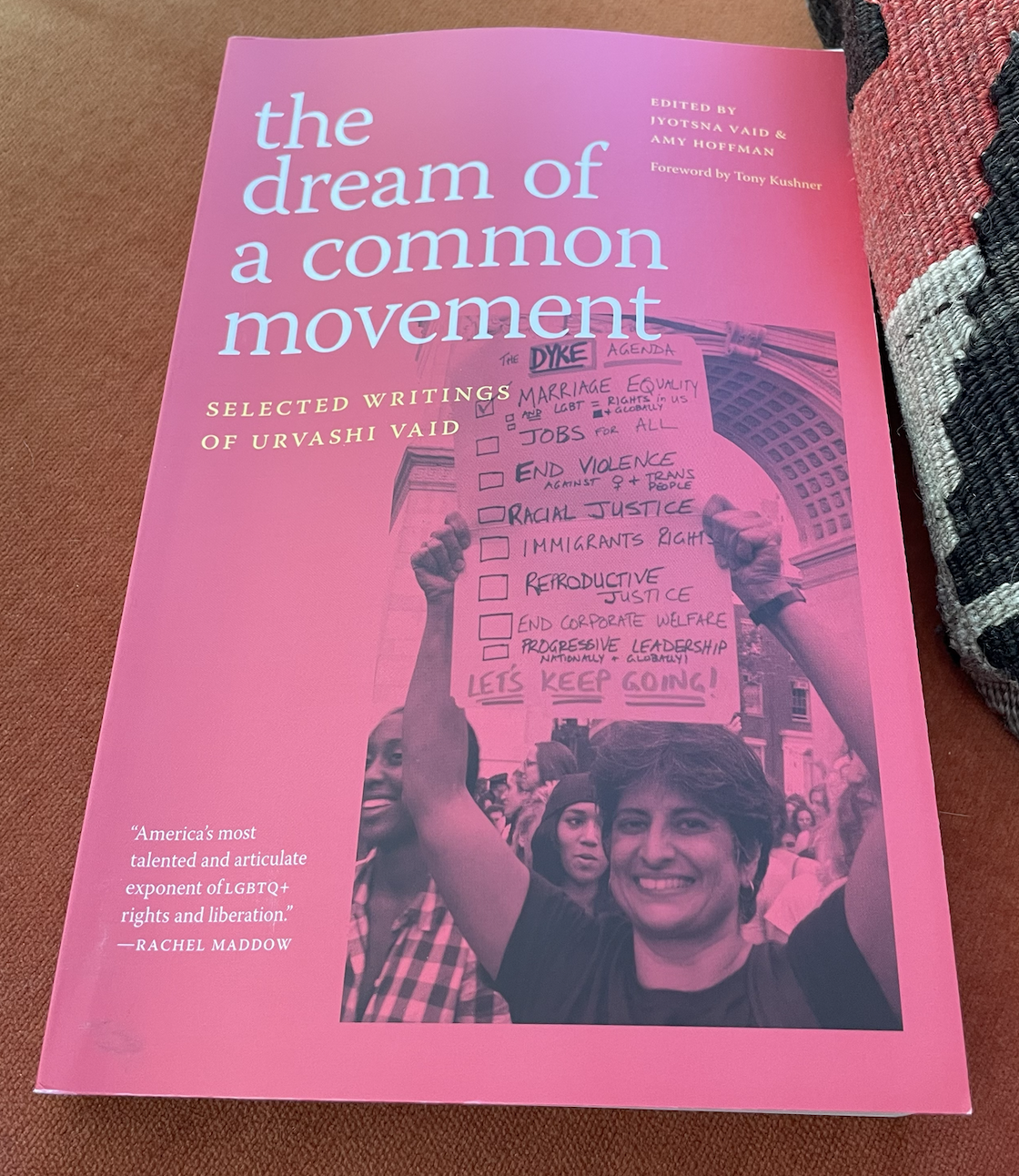

Image description: The Dream of a Common Movement: Selected Writings of Urvashi Vaid Edited by Jyotsna Vaid & Amy Hoffman Foreword by Tony Kushner Blurb from Rachel Maddow: "America's most talented & articulate exponent of LGBTQ+ rights & liberation." Picture of a smiling Vaid holding up a sign (photo is by Donna Aceto & title is Urvashi at Dyke March, 2011): The DYKE AGENDA with the top item MARRIAGE EQUALITY checked Followed by a long list of other items not checked: JOBS for ALL END VIOLENCE RACIAL JUSTICE IMMIGRATION RIGHTS REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE END CORPORATE WELFARE PROGRESSIVE LEADERSHIP (nationally + globally) LET'S KEEP GOING! Since we seem to be regressing, this list is helpful for the present moment!

The collection has been compiled and edited by one of Urvashi Vaid’s sisters, Jyotsna Vaid, and her former lover and long-time friend, the writer Amy Hoffman. As the title The Dream of a Common Movementsuggests, the book documents Vaid’s ongoing work of creatively imagining, building, and sustaining an LGBTQ+ political movement. The collection opens with a brief Foreword from playwright Tony Kushner, who calls it “a book of essays of practical politics” (xiii), and an introduction from the editors, who emphasize Vaid’s canny understanding that “it was imperative for a movement to articulate its vision of a better world, to know what it is fighting for,” as well as “knowing whose vision it is fighting against” (7). The editors explain that, even in the final months before her death from breast cancer in May 2022 at the age of 63, Vaid was organizing the 22nd Century Initiative to Counter Authoritarianism, because she “saw early on the existential threat the highly organized right-wing, autocratic movement in the United States and globally posed to individuals, to progressive movements, and to democracy itself, and devoted a good part of her efforts to organizing a broad-based movement on the Left that affirmed and protected democratic institutions and civil liberties” (7). Many of the speeches and essays in Dream of a Common Movement are from the 1990s and early 2000s, yet they are eerily prescient about the regressive and repressive forces working against the expansion of rights for, and indeed the very humanity of, LGBTQ+ people in the US and around the world, forces that have been seeking to consolidate power since Trump’s second inauguration.

The Dream of a Common Movement is organized into four parts: Building a Movement, Expanding Its Scope, Taking Stock, and The Promise—and Precarity—of Justice. That the book ends with a section that formulates the promise of justice as always threatened to be interrupted by its precarity is, I believe, a helpful way of framing our current moment, and this dual analysis indicates why Vaid’s thinking-writing-activism continues to be so relevant and necessary. The framing of justice both as a promise and as precarious also foregrounds what I would call the multiple temporalities of politics that Vaid articulates both conceptually and pragmatically. The quote that opens this review—“I believe social change happens both incrementally and in flashes of illumination.”—is taken from a 1998 interview by David Barsamian for his Alternative Radio program. For Vaid, even if we experience flashes of illumination through transformative personal and political experiences (her example in the interview is the experience of coming out), the work of politics is always more than these moments, and requires that we keep going, even or especially after a flash of illumination or a political win. The image of Vaid on the cover of Dream of a Common Movement exemplifies the multiple temporalities of politics. A photograph by Donna Aceto titled “Urvashi at Dyke March” and taken in 2011 shows Vaid smiling broadly and holding up a sign, headed “The Dyke Agenda” with a checklist below. The top agenda item is Marriage Equality and this box is checked. Below this checked item is a long list of unchecked items, including Jobs for All, Racial Justice, Immigrant Rights, Reproductive Justice. The tagline, underscored several times, says “LET’S KEEP GOING!” This image and slogan encapsulate Vaid’s vision of the ongoingness of politics, and the joy that comes from keeping going as politics.

Vaid was born in New Delhi, India in 1958, and she and her family emigrated to Potsdam, New York in 1966, when her father took a faculty position at the State University of New York at Potsdam. In the preface to her 1993 book Virtual Equality, excerpted here as the opening chapter on her “Formative Influences,” Vaiddescribes her parents’ uncertainty about her chosen path. She explains that their unease was less about her lesbianism and more about her decision to become a professional activist (not a typical path for a daughter of immigrants from India). Yet, what comes through in the collection is pride in the daughter/sister who opted for a riskier path for an immigrant daughter, and one that ultimately gave her an extended community even amid the devastation of the AIDS crisis and the rise of a right-wing movement determined to counteract the expansion of rights for LGBTQ+ people.

The AIDS crisis is at the center of Vaid’s work and life. The final chapter in the opening section on Building a Movement is entitled “Awakened Activism: AIDS and Transformation,” and is an edited version of chapter 3 of Vaid’s book Virtual Equality: The Mainstreaming of Gay and Lesbian Liberation published in 1995. Revisiting Vaid’s notion of awakened activism and her critical concept “virtual equality,” which Vaid defines here as “a partial, conditional, simulacrum of equal rights” (160), provides an antidote in the present moment to the right’s glib trolling of “wokeness.” The difference between wokeness and awakening matters. While wokeness implies an arrival at a state of enlightened consciousness, awakening draws on the earlier feminist concept and practice of consciousness raising and emphasizes an ongoing process of becoming awakened. For Vaid, this process of becoming happens through bringing together thought and action in activism.

Vaid’s “Awakened Activism” begins with her describing meeting long-term partners Walta Borawski and Michael Bronski in Boston when they all worked together at the collectively run Gay Community News (GCN) in what Vaid calls “that time before AIDS” (62). Vaid movingly describes her relationship with the two men in this way: “They seemed so much older, although they were only in their thirties. They became two of my mentors in gay and lesbian liberation and, in a way, I grew up with them” (62). Vaid continues, noting that they “became friends through endless arguments, all trying to define what progressive gay and lesbian politics meant” (62; emphasis in original). AIDS interrupts these arguments about politics and changes everything. Looking back, as she writes in the early 1990s, Vaid plaintively asks, “When did it all change? When did our lives go from the optimism of people developing a whole new politics to the numbness of a people experiencing survival as a disaster?” (63). “Was it the year that Walta started to fade?” Vaid wonders and then continues with a long litany of other painful losses, desperately trying to pinpoint the exact moment when everything changed. But of course, there is not one moment, but hundreds, thousands of moments for people around the world, moments that together make up the catastrophe that was and continues to be the AIDS crisis. For Vaid and her community of young activists in Boston, AIDS creates a cut in time, both personal and political, marking “two distinct eras: Before AIDS and After AIDS” (64). Vaid then explores what I am calling the multiple temporalities of activism. She notes that, “In the 1980s, gay and lesbian advocates made four strategic choices whose results affect us to this day: degaying, desexualizing, decoupling AIDS-specific reform from systemic reform, and direct action. At the time, those decisions seemed the best responses we could come up with, but they were short-term, quick-fix strategies that yielded dramatic but short-lived gains.” Looking back at early AIDS activism, Vaid diagnoses a short-termism that, perhaps inevitably, “failed to tackle the underlying problems that still exacerbate the epidemic: the problems of homophobia, sexual denial and repression, racism, sexism, and the dictates of a profit-driven health care system” (64).

Reading Vaid on “virtual equality” in the 1990s is instructive in 2025. We know now that, under Trumpism, the hard-won gains LGBTQ+ activists fought for in the 1990s can be and are being reversed. We are witnessing a regression to an earlier moment of brutal stigmatization rather than continued progress in tackling the AIDS epidemic worldwide. Yet, reading Vaid now, for me, is not disheartening, but invigorating in its insight into doing politics across multiple spaces and temporalities. Across the pieces in Dream of a Common Movement, Vaid eschews single-issue identity politics in favor of a “holistic response” (109). In a very moving keynote address she gave at her alma mater Vassar College in 2011, on the 150th anniversary of the college, Vaid discusses class politics and the LGBTQ+ movement. She begins with this personal observation about the relationship between cultural capital and economic capital: “Vassar changed my socioeconomic class status forever, from immigrant working-class to upwardly mobile and securely middle-class” (126). The title of Vaid’s address is “Assume the Position,” and she deftly explores how “class positions embody and generate a way of seeing and being seen,” adding that “like all observation and experience, this way of seeing is raced and gendered. Socioeconomic class affects whom or what you notice and with whom you affiliate” (126-127). She then goes on to describe the mismatch between the class composition of LGBT communities and those “people who staff, fund, and lead our movement’s mainstream institutions” (131), an observation still very much relevant today. She discusses recent studies at the time showing, for example, that “trans people are nearly four times more likely to live in poverty than the general population” (131). She also reports on studies showing that LGBTQ+ youth are more likely to be homeless than non-LGBTQ+ youth, and that in general, according to a Queers for Economic Justice study, “Most participants reported very high levels of police harassment, violence, and harassment by government agencies” (132).

Trained as a lawyer, Vaid had an impressive career in LGBTQ advocacy and philanthropy, including in various leadership positions in the National LGBTQ Task Force and as a deputy director of the Governance and Civil Society Unit of the Ford Foundation. Thus, her critique of what she called the “class-based access” politics of LGBTQ organizations like the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) comes from her own observations and experience negotiating these spaces from the outside in. She ends the Vassar speech by describing what she calls “queer practice” in action, which again for me emphasizes the ongoingness of politics and both the affective and material benefits of this work. “Queer practice—LGBT life in its widest range—,” Vaid asserts, “builds curious and sometimes marvelous communities. Our subcultures turn pain into caring; our institutions deliver services, resilience, and humor instead of bitterness and violence; our extended kinship structures deliver emotional and material support, independent of blood ties.” The Dream of a Common Movement provides a vision of queer practice and is itself a resource in the ongoing process of building a curious and marvelous community in the face of authoritarianism.