Yard work in Kevin Adonis Browne’s A Sense of Arrival

A self-portrait of the author looks out from the brown-black cover of Kevin Adonis Browne’s magnificent new book A Sense of Arrival. The cover image is also placed at the very center of the book as part of a series of eight photographs that form a visual entryway into a section entitled “Self.” The photograph on the cover is titled Self Invention; or, History of a Skin Wrapped in Brown Paper, No. 4 and in the opening sentence of “Self,” Browne asks, “Do you ever feel yourself becoming an archive of the promise that was made when your portrait was first produced?” (207). This doubling of portraits of self invention on the cover and in the middle of A Sense of Arrival encapsulates the assemblage of forms and modalities and concepts and methods brought together in Browne’s book. Browne’s portrait and query create a verbal and visual direct address to a reader whose arrival Browne can only sense, leaving open the possibility—inevitability—of future encounters. The author’s self-portrait on the cover looks out at the reader but also to the side of the reader, as if in anticipation of other readers to come. Browne’s book is an exquisite demonstration of Black study in action. Echoing a phrase from Browne’s poetic chapter “Form” that describes how Calypso singers “show us a form” (280), we might say that Browne’s Sense of Arrival shows us a form, or the multiplicity of forms that is Blackness and Caribbeanness. This is a book to read slowly from cover to cover but also to dip in and out of—to sit with, but also to put aside and come back to.

Kevin Adonis Browne’s A Sense of Arrival.

Cover image is a self-portrait of the author entitled Self Invention; or, History of a Skin Wrapped in Brown Paper, No. 4 .

In the spirit of Browne’s own creative use of footnotes (including footnotes within footnotes) to move the reader in and out of the flow of super- and sub-texts, in this reading notes post, I want to offer a brief note on one short chapter in Browne’s book that I argue provides a method-image of Hortense Spillers’s theorization of Blackness as vestibular to western, colonial, patriarchal culture (Spillers 1987, 67). Browne’s chapter is entitled “Yard,” and it appears in the middle of the penultimate section of A Sense of Arrival. According to Merriam-Webster dictionary, a vestibule is “a passage, hall, or room between the outer door and the interior of a building,” and Spillers uses this term to indicate a threshold space that enslaved women occupied in what Imani Perry describes in Vexy Thing as the “architecture of gendering and the construction of patriarchy in modernity” (Perry 2018, 37). Vestibule is also an anatomical term meaning “any of various bodily cavities especially when serving as or resembling an entrance to some other cavity or space.” Vestibularity, then, is for Spillers a concept-metaphor for the cut between inside and outside, private and public, body and culture, flesh and human. A vestibule separates but also connects—it is a liminal space that is also potentially a passage into new ways of being and living, and into new genres of the human, as Alexander G. Weheliye argues, drawing on the work of Sylvia Wynter (Weheliye 2014, 44).

A yard is a vestibular space, both inside and outside of the home, and extending the idea of home out into the world. Or, as Browne puts it in “Yard,” yard is a “trope and repository of motion and the stretching of space over time, the transposition of being here and there. Yard as transcendence beyond the very concept of boundary. Yard, too, as rhetorical device. And as artistic method. This should come as no surprise. Our earliest experiences arrive in the shape of structures that hold us” (319). Browne tells a story of the yard in Trinidad that held and holds him still, and the chapter “Yard” includes two black-and-white snapshots of the author as a child in the yard with members of his family. As Browne explains, “This is not the house I grew up in but the house I grew up around. I grew up, you could say, mostly on the outside of it” (319). This idea of growing up around a house suggests the phenomenological experience of what D.W. Winnicott described as a “holding environment”—those structures that support and constrain us in the process of becoming our selves. Yet, for Browne, this is not a general theory of psychic development, but the “memory of home that feels like blackness, like Caribbeanness to me,” as captured in a photograph of himself and two cousins sitting together on a porch railing in, and framed by, the yard (323). Browne “comes back to see what there is to see” in the photograph, noting that the “former bodies and bodies formerly known as ‘cousin,’ and ‘cousin,’ and ‘self,’” are “shown here as a singularity perched between the here and the there of the yard, on the cusp of inside and outside” (322). A singularity of this yard that held Browne and his cousins, but also a theory and practice of yard work made manifest in this couplet that forms a passageway out of “Yard”:

My blackness is a manifestation of the yard.

My Caribbeanness is made in the yard, made of the yard itself (324).

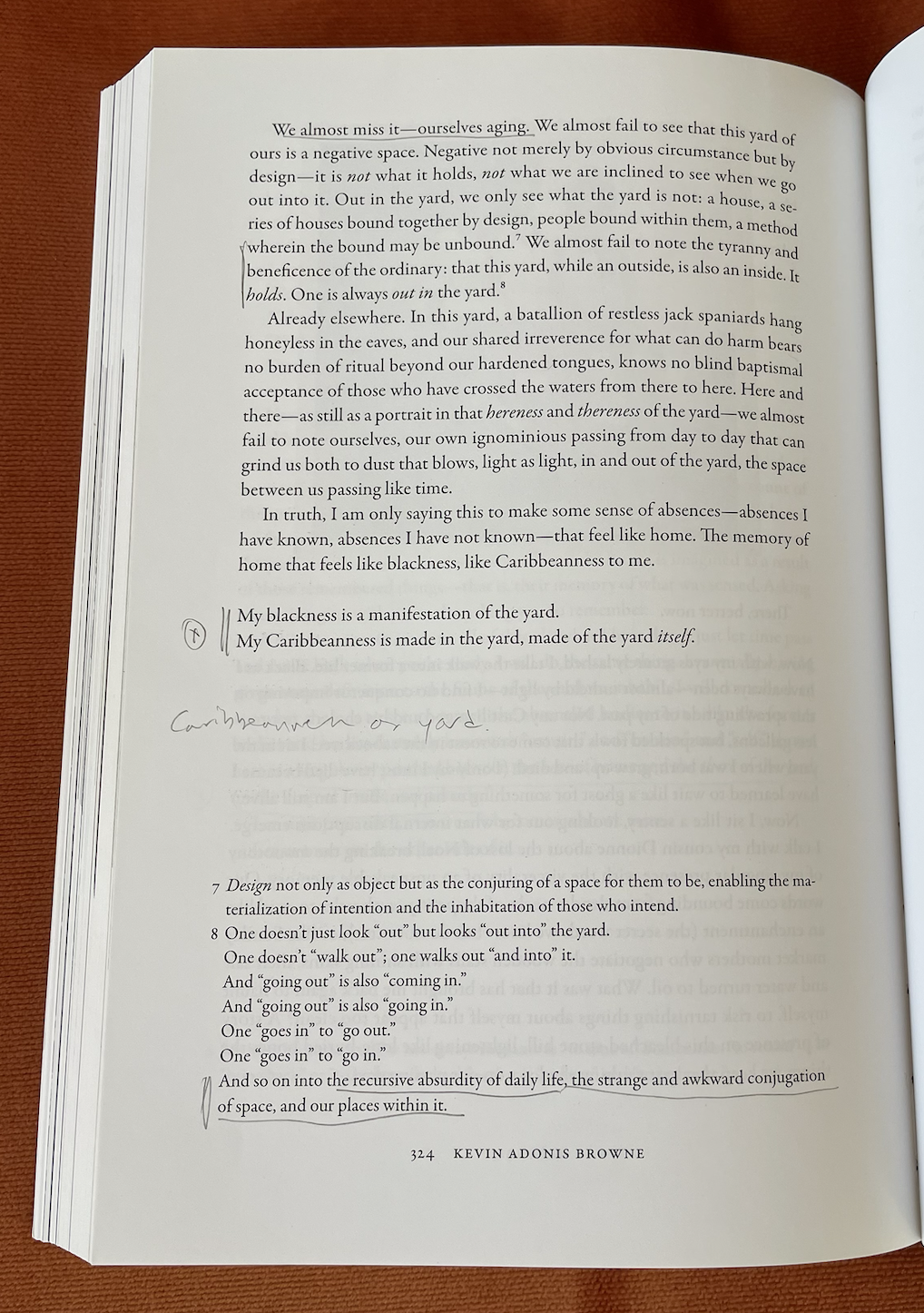

Page 324 from Kevin Adonis Browne’s A Sense of Arrival

The page has main text and footnotes. This reader has underlined and annotated the page with the note “Caribbeanness as yard.”

Citations

Browne, Kevin Adonis. A Sense of Arrival (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2024).

Perry, Imani. Vexy Thing: On Gender and Liberation (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2018).

Spillers, Hortense J. “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diacritics 17, no. 2 (Summer, 1987): 64-81.

Weheliye, Alexander G. Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2014).