Alice Wong: #SuckItAbleism

I woke up this morning to the devastating news of Alice Wong’s passing. As with everything she did, Alice marked her own passing with ferocity and humor, ending a statement posted by her friend Sandy Ho on her Instagram account with the words, “I’m honored to be your ancestor and believe disabled oracles like us will light the way to the future. Don’t let the bastards grind you down. I love you all.”

This is a first attempt to say something about what Alice and her work means to me.

Like so many others around the world, I first made Alice Wong’s acquaintance on Twitter. I fondly remember Alice responding to a post of mine during an early #CripTheVote twitter chat in which I referenced Pierre Bourdieu’s metaphors of capital as a framework for thinking about chronic illness and disability. In her smart and sassy way, Alice gave an enthusiastic shout out to Bourdieu, which surprised and amused me. I would later learn Alice had started a PhD in Sociology, which she hadn’t been able to finish because her progressively disabling condition and the ableism of academic life prevented her from continuing. Yet, undaunted by the ableist habitus of academia, Alice would go on to become one of the foremost thinker-writer-activists of the 21st century, bringing disability to the forefront of conversations about politics, art, and media in the U.S. and around the world. She was an incomparable force for disability justice and community, and the heartfelt outpouring of love and appreciation for her and her work on social media today shows the profound personal and political impact she has had, and will continue to have, on people and politics far and wide.

Alice had a huge influence on my thinking, writing, and teaching about disability from the moment I began participating in #CripTheVote twitter chats and listening to her Disability Visibility Project podcast. In the epigraph to my book Illness Politics and Hashtag Activism, I quote Alice’s words from a Disability Visibility Project podcast with her #CripTheVote collaborators Gregg Beratan and Andrew Pulrang: “The revolution is here. One podcast, one transcript, one tweet at a time.” I also give a special shout out to Alice in my acknowledgments to that book, noting she is “a force on social media—smart and incisive in her critiques of ableism and warm and welcoming in her creation of online community for disabled people and their allies.” And because we all know it's true, I added, “She may be the best coiner of hashtags I know. One of my favorites is #SuckItAbleism, a hashtag she started to point to the absurdity of plastic straw bans to stem the tide of climate change.” In my grief and rage at her passing, #SuckItAbleism is the phrase I offer in place of #RIP.

My analysis of the hashtag #CripTheVote is at the center of Illness Politics and Hashtag Activism, and I argue that #CripTheVote’s influence on politics in the U.S. was nothing short of transformative. Through Twitter chats beginning in 2016, Alice and her collaborators had a profound impact on bringing disability to the center of mainstream political conversations. In the 2020 campaign, both Elizabeth Warren and Pete Buttigieg participated in #CripTheVote Twitter chats. #CripTheVote was also concerned with emphasizing the intersectionality of disability experience, both in terms of the many kinds of impairment under the disability umbrella, as well as the many ways race, gender, class, and sexuality inflect disability experience and vice versa. They made a space for a wide variety of people to share their disability experiences, as well as for discussion of how white supremacist and heteropatriarchal systems function through ableist attitudes and disabling structures. Put simply, as I write in Illness Politics and Hashtag Activism, “#CripTheVote has generated a more nuanced and widespread understanding of how ableism operates, and how it can be counteracted, in politics.”

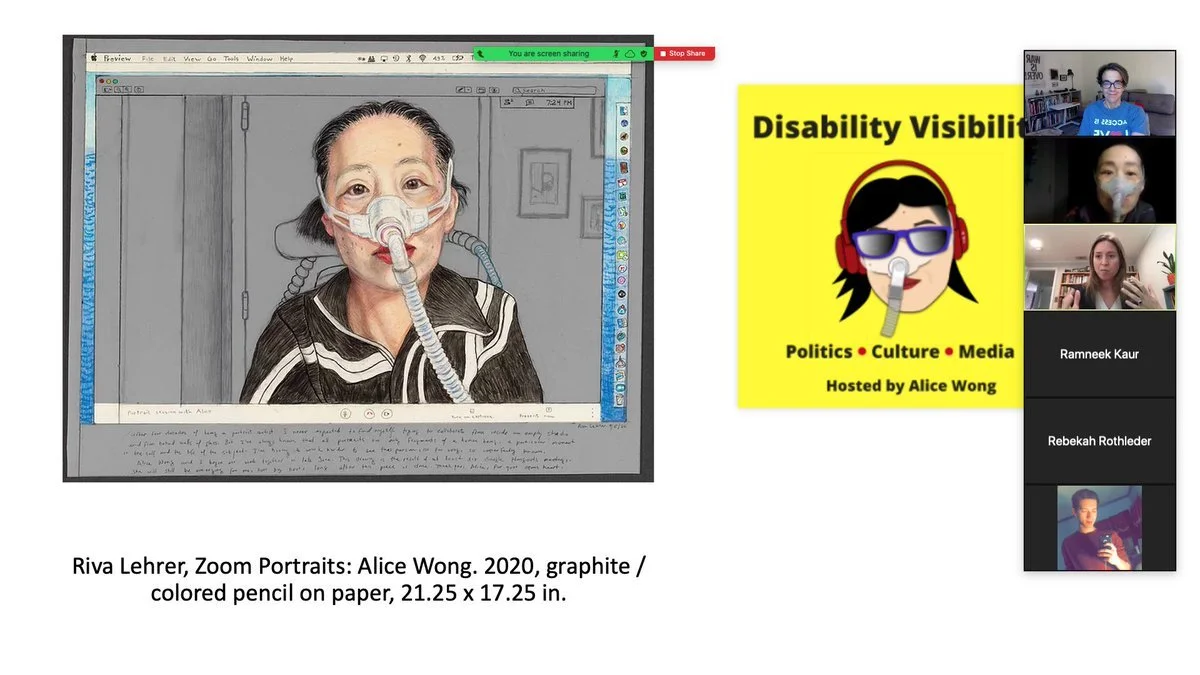

Figure 1: Screen grab of zoom event featuring Alice Wong as part of the Pressing Matters series at Stony Brook in October 2021. On the zoom screen is Riva Lehrer’s Zoom Portraits: Alice Wong. 2020, graphite/colored pencil on paper, 21.25 × 17.25. To the right of Lehrer’s portrait of Wong is Alice Wong’s Disability Visibility avatar on a bright yellow background. Further to the right is a are zoom boxes with Lisa Diedrich in a Access is Love t-shirt, Alice Wong, and Karen Lloyd, who is asking Wong about her experience working with Lehrer on the portrait.

In 2021, my colleague Karen Lloyd and I hosted Alice for a zoom talk in the Pressing Matters series in the Humanities Institute at Stony Brook. As part of a larger interdisciplinary initiative on Pandemic Narratives, we decided we wanted to bring in speakers doing pathbreaking work in imagining new ways of telling stories, and Alice Wong was the first person we thought of who was doing this transformative kind of work. There was a curricular component to the event. Students in my Life/Death | Health/Justice class read parts of Wong’s edited volume Disability Visibility and students in Karen Lloyd’s Art & Medicine class studied painter Riva Lehrer’s stunning portrait of Wong (Figure 1) and discussed pandemic portraiture, as well as disability in the visual arts. They helped us prepare for the conversation and Alice was clearly moved by their questions and engagement with her work. The Stony Brook student newspaper The Statesman covered the event with an in-depth article, including this moving quote from one of the students in Prof. Lloyd’s Art and Medicine class: “’[Wong’s] 2018 episode with W. Kamau Bell was such a pivotal piece of media for my parents in understanding the impact of disability on my life,’ Ramneek Kaur, a junior biology major said.”

Figure 2: Selfie of Lisa Diedrich and Alice Wong hanging out at a cafe in San Francisco in 2018

Alice and I met once IRL in San Francisco in 2018 at a café in the Mission District near the place she shared with her parents (Figure 2). I briefly met both her parents and want to extend my deepest condolences to them and her two sisters. I have lately been thinking and writing about the concept and practice of ongoingness as a chronic form. Alice’s memoir Year of the Tiger is an example of this practice of ongoingness. In a beautiful chapter “About Time,” Alice describes how, in putting together her memoir, she “realized life is one never-ending edit.” She ends the piece with the reality that “only death wins in the end.” Yet, her work is ongoing into the future: “Slow or fast, people can find me in these words and the spaces in between long after I’m gone.”