The Politics and Poetics of Citation

In the spring I taught my Feminist Interdisciplinary Histories and Methods graduate seminar. This is a favorite class of mine to teach because it allows me and my students to explore questions of method—that is, both practical and theoretical questions about how we do scholarly research, writing, and presentation. For me, this involves formal questions: What shape does our work take? What materials do we include or leave out? How do we assemble and arrange the different components of our work? Many of the readings for the seminar present formally creative models of interdisciplinary research and writing, which I hope will help students conceive of their own work outside of the box of the traditional dissertation format. In this way, I understand the seminar as drawing on and expanding recent efforts to support “next generation-dissertations,” as colleagues at Syracuse University with funding from NEH have termed the growing movement to develop new approaches to and formats for doctoral research.

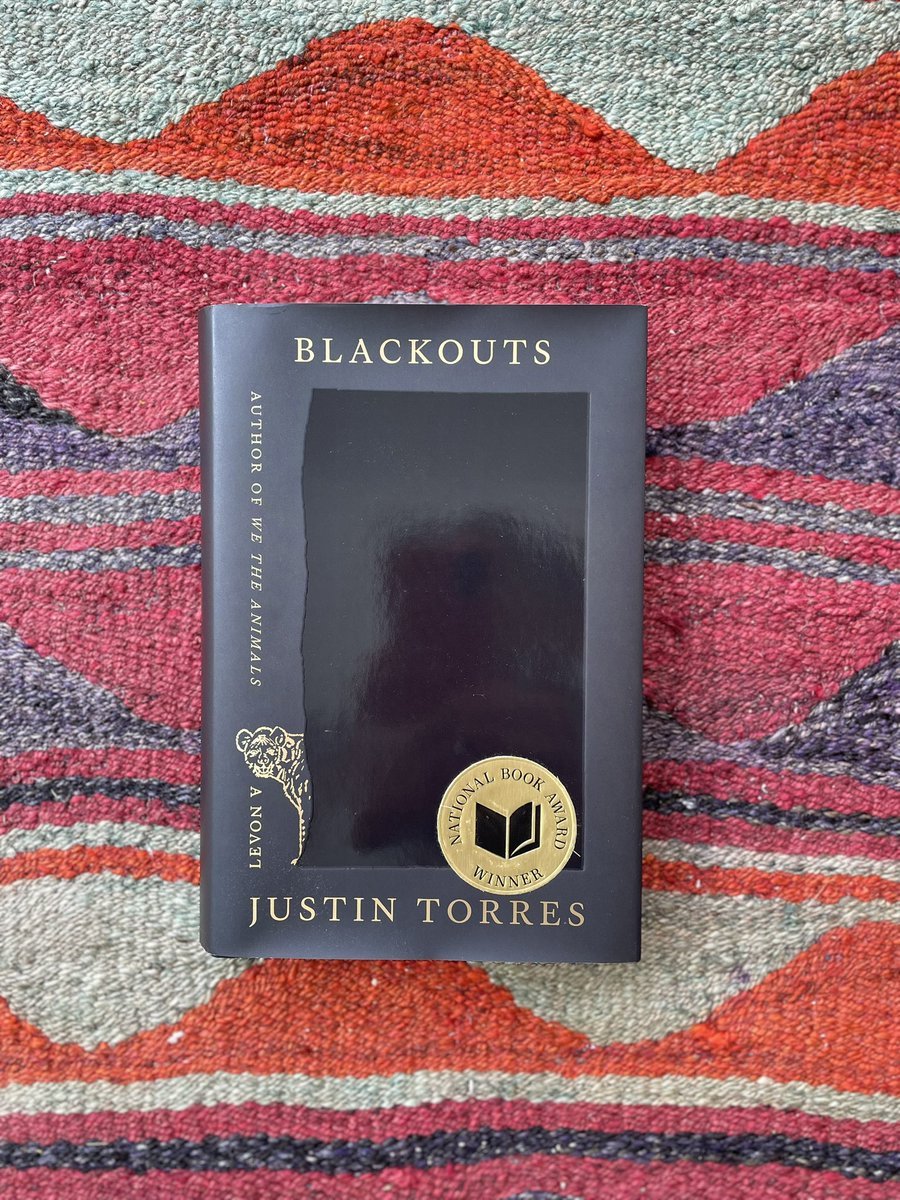

In this Reading Notes blog, I will discuss a prominent theme that came up in our seminar discussions regarding what I call the politics and poetics of citation—that is, both the politics of what and who we cite, and the aesthetic forms citation takes. I then turn briefly to Justin Torres’s new novel Blackouts and his use of “blinkered endnotes” as another example of formally inventive citation practices. As with my other Reading Notes blogs, I don’t offer a comprehensive review of Torres’s novel, which won the 2023 National Book Award for fiction, so much as engage with a formal aspect of the work that intrigued me, especially in relation to discussions in the seminar I had just taught. I always treat myself to a new work of fiction at the end of a semester of teaching. In this case, I was struck by the fact that Blackouts could have been (and may be in the future) a text I would teach in Feminist Interdisciplinary Histories and Methods.

Torres’s work felt to me like it continued many of the conversations we had had in our seminar about form, evidence, and “critical fabulation,” to use Saidiya Hartman’s term for her practice of troubling the line between history and imagination. And, indeed, Torres cites Hartman in his endnotes in reference to an “image of a woman with flowers,” a photograph of the actress Edna Thomas included in Blackouts. Torres writes, “For more about Edna Thomas, read Saidiya Hartman’s transcendent chapter on the actress in her book Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments. One of the sources Hartman draws upon is Edna’s testimony in the Sex Variants study, where she participated under the pseudonym Pearl M. It is Pearl’s story that was chosen to begin the second volume of the study, WOMEN” (287). Jeannette Foster’s Sex Variant Women in Literature from 1956 is one of the key historical sources around and through which Torres creates the “work of fiction” (295) that he insists, in “A Sort of Postface” at the very end of the book, Blackouts is, despite its reference to real historical figures and events. More on Blackouts to follow in a sort of postface to this Reading Notes blog, but first some thoughts on my seminar.

You can find the syllabus for the seminar here. Over my many years of teaching, I have enjoyed experimenting with the syllabus as a genre, and my graduate methods seminar is no exception. I structure the syllabus around key terms and concepts, methods, and case studies, and I incorporate quotations and images from the texts we read, watch, and listen to, attempting to enact in the syllabus itself the multi-modal reading practices we engage with in the seminar. Most of the texts for the class are themselves multi-modal—combining words, images, music, prose, poetry, drawings, diagrams, etc.—to capture the multiplicity of experiences and events in history.

I introduce the syllabus with an image. In the winter break before the spring semester, I had seen Ruth Asawa’s show “Through Line” at the Whitney Museum, and I appreciated that the show emphasized how Asawa’s “exploratory approach to materials, line, surface, and space yielded an impressive range of drawings that speaks to her playful curiosity and technical dexterity as well as her interest in the aesthetic possibilities of the everyday.” Thus, I used a work of Asawa’s, “Untitled (BMC.127, Meander in Green, Orange, and Brown), c. 1946–49,” to serve as a kind of epigraphic method-image for the syllabus—opening up the possibility of the seminar as a methodological meander, suggesting both the noun (a winding path or course) and verb (to wander aimlessly or casually without urgent destination) forms of the word.

Our seminar discussions meandered into questions of form, accessibility, and modality. To my surprise and pleasure, some students were listening to audio versions of some of our texts, which generated diverse reading/listening experiences. For example, I learned that the audiobook for Christina Sharpe’s brilliant Ordinary Notes is narrated by Sharpe herself intermixed with a sound scape created by artist Ain Bailey. Thus, our method-images multiplied throughout the semester: verbal, visual, sonic, and moving across spatial and temporal scales.

I juxtaposed two texts I love in the middle of the course—Katherine McKittrick’s Dear Science and Other Storiesand Max Liboiron’s Pollution Is Colonialism—as examples of science studies in action and as foregrounding Black and anticolonial methodologies, respectively. In both texts, footnotes, and citation practices more generally, are thematized. In the chapter “Footnotes (Books and Papers Scattered about the Floor),” McKittrick explains, “This is a story about citations, endnotes, footnotes, notes, references, bibliographies, texts, narratives, parentheses, sources, and pages. It is a story, one of many, about what we do with books and ideas. It is a story about how we arrange and effectuate the ideas that make ideas.” (15) In this chapter about footnotes, I encouraged the students to pay attention to McKittrick’s own footnotes, which create a sly meta-performative element, as one footnote, for example, references the importance of carefully reading Fanon’s footnotes (19, footnote 19). Footnotes as meta-meander.

The question of accessibility also came up in relation to McKittrick’s footnotes. We discussed the experience of reading her extensive footnotes—how they force the reader to switch between main text and footnote text, which can be distracting, as well as how the density and length of material contained in the footnotes was sometimes overwhelming, causing some readers to lose the flow of the main text. In McKittrick’s text, some footnotes go on for several pages, displacing the main text and creating a textual inversion of the relationship between our ideas and the ideas that make our ideas.

As with Dear Science and Other Stories, footnotes play a key formal role in enacting the ideas of Liboiron’s Pollution Is Colonialism. For the most part, students found Liboiron’s footnotes more accessible, which seemed to be mainly a matter of style and mode of address. Students appreciated Liboiron’s humor as well as their performance of gratitude and generosity towards their interlocutors. In a footnote in the Acknowledgements, Liboiron explains, “I see these footnotes as enacting an ethic of gratitude, acknowledgement, and reciprocity for their work” (viii). And in the first footnote in the text itself, Liboiron writes, “The footnotes are a place of nuance and politics, where the protocols of gratitude and recognition play out (sometimes called citation), where warnings and care work are carried out (including calling certain readers aside for a chat or a joke), and where I contextualize, expand, and emplace my work. The footnotes support the text above, representing the shoulders on which I stand and the relations I want to build. They are a part of doing good relations within a text, through a text” (1). Doing good relations is enacted as a kind of method in both the form and content of Liboiron’s work.

Towards the end of the semester, we read Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, and here again, the politics and poetics of citation was a key theme. Interestingly, some students found it problematic that the endnotes are unmarked in the main text, pointing out that they could easily be missed by readers. I explained that I thought this was most likely because Hartman’s book is published by a trade press and thus meant for a more general readership less habituated than academics to reading endnotes. I also argued that the notes are there to be discovered, which for me seemed to enact formally a “desire for an elsewhere and an otherwise” (46) that Hartman identifies in the young Black women whose stories she tells in the book. These not-readily-apparent citations enact a kind of meander, a path that might be belatedly or unexpectedly traced. As one example of this possibility, I pointed to the note linked to the sentence “Mabel Hampton still imagined that she could live a beautiful life” (297), which cites the Mabel Hampton Oral History Collection at the Lesbian Herstory Archives, and adds this description of Hampton: “Mabel was an archivist and collected playbills, scrapbooks, photo albums, black postcards, and musical theatre programs” (411). Hampton not only imagined that she could live a beautiful life, but she also documented that life and worked to create an archive (both the materials she collected and the space and project of the Lesbian Herstory Archives that houses her collection, among many others). Hartman, then, nests Hampton’s story, archive, and story of an archive in her book Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments.

And now for a “sort of postface” about citation in Justin Torres’s Blackouts. Imagine my delight when I picked up Torres’s novel and discovered, along with references to Hartman’s work, a hybrid and genre-bending book combining words and images and practicing redaction (blacking out) as method. When I reached the “Blinkered Endnotes” at the end, I initially thought this was a term for endnotes not marked in the text, as in Hartman’s Wayward Live, Beautiful Experiments. But no, “blinkered endnotes” is a term Torres appears to have invented to suggest his method of historical and literary analysis. Torres describes a conversation with his (real or imagined?) friend Juan in which Juan says, “the past is always surfacing, always lurking, just there, in your peripheral vision” (283). Torres tells Juan he doesn’t know how to look at the past, and admits he “felt blinkered,” like an easily spooked racehorse. When Juan dies, he leaves Torres “with these documents and photos and medical texts, glimpses of sublimated history.” Torres explains his encounter with these materials, “when I tried to pull out and look at the past with wide vision, I found it difficult to see. So these endnotes are not scholarly, but personal, glancing” (283, italics in original). I was struck by how the personal, glancing was offered as an alternative to the scholarly as another form of the politics and poetics of citation.